“Homework is one of the most stressful parts of a family’s day,” says Elizabeth Garraway, principal at P.S. 118: The Maurice Sendak Community School in Park Slope, Brooklyn. “Families argue about homework and instead of being something that kids enjoy or something they learn from, it becomes a source of stress for parents and for kids.”

At School Leadership Team meetings last year, parents kept bringing up concerns regarding homework. “A lot of families were feeling like the homework was kind of making their children feel under pressure or frustrated after school,” says Alexis Hernandez, a first-grade teacher at P.S. 118.

These sentiments about homework are not unique to P.S. 118.

Homework has been “a part of the discussion around education throughout the 20th century as people debated what should kids be doing in school and what should kids be doing outside of school,” says Thomas Hatch, Ed.D., co-director of the National Center for Restructuring Education, Schools, and Teaching. “I think the latest incarnation of the concerns about homework has come along with the concerns of the proliferation of testing. So, I think, right now concerns about homework, concerns about testing, concerns about academic pressure on kids are all kind of coming to the forefront.”

While those concerns are being voiced, there is a huge divide in this country among parents. There are “parents who are very focused on high academic achievement and really push their kids. Those are the parents who want homework,” says Etta Kralovec, Ed.D., author of The End of Homework: How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, and Limits Learning. “And then there’s another group of parents who want their kids to have well-rounded lives, who want their kids to be involved in church activities, or they want their kids to be in Scouting.”

With the regular school day, extracurricular clubs and activities, and sports teams, many parents and students are lamenting how much time homework takes, and parents and educators are questioning whether it really benefits the kids.

RELATED: Help Teens Deal with Stress

Finding a Balance

Hatch doesn’t think teachers should stop assigning homework altogether, but should work to find a balance between activities that support academic development and activities that support other aspects of development.

“My take on that is really to look at it in the broader perspective. It’s not just about homework per se, it’s about how much time and focus do we want to see kids having on academic activities,” says Hatch, who is also a professor at Teachers College, Columbia University. “It’s really about how do we create a balance between a focus on academics and activities to embrace a wider set of abilities.”

The question of balance isn’t just a hot topic in the U.S.; there are debates going on in many countries, including Korea, China, and Singapore, according to Hatch. The concern is kids are spending too much time in tutoring centers. “It’s kind of like an educational arms race where the parents are concerned about kids spending too much time outside of school cramming for tests …but at the same time they’re worried that if they don’t put their kids into those centers or don’t support continuing their academic focus after school, then those kids are going to fall behind,” Hatch says. “That’s in part what you see in the U.S. as well.”

It’s possible to find that balance with and without homework, Hatch says. If students are spending their entire school day on reading, math, writing—the basic academic skills—and going home with worksheets, “that’s a problem,” he says. If, on the other hand, students have time for recess, play, music, and art during the school day, it’s okay, developmentally, for them to have some homework relating to their academic work.

|

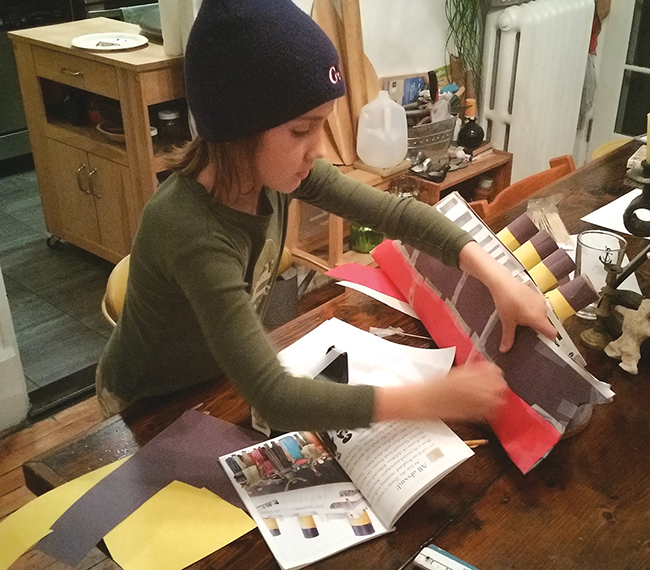

Courtesy Oliver Stockhammer

|

|

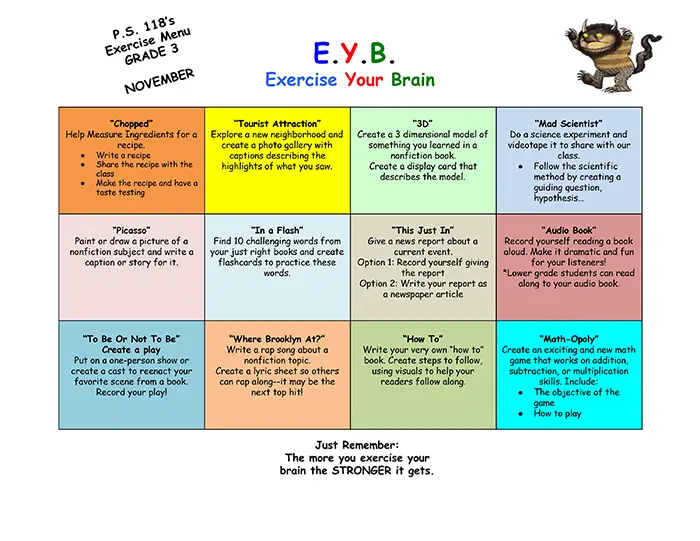

Jovan Stockhammer, a third-grader at P.S. 118: The Maurice Sendak Community School in Park Slope, Brooklyn, works on creating a 3-D model of the Titanic as part of the school’s Exercise Your Brain program, which replaced traditional homework this year.

|

Ending Homework

“I don’t see any benefit to keeping homework,” says Kralovec, who is also an associate professor of Teacher Education and the program director of Graduate Teacher Education at the University of Arizona South. “There’s just no research that says it develops any kind of abilities or characteristics in student behavior that they actually need in life.”

At the elementary level, there is no research that shows homework increases academic achievement. “In fact, most of the research says that it’s detrimental to kids because they’ve been in school all day and they need to exercise other parts of themselves other than just their school self,” Kralovec says. “I think that’s why a lot of elementary schools are really looking at getting rid of it.”

At the middle- and high-school levels, though, the research is less clear that homework doesn’t support academic achievement. “There’s a correlation between homework and grades, but the correlation is very weak. Homework may be part of a good student practice by the time you get to high school, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that the homework is actually effective,” she says.

With the proliferation of articles in the past few years about school-induced stress, we know today’s students feel significant pressure to achieve—especially kids who want to go to college and think they have to be involved in various activities and in the community. Kralovec says homework, in some way, impedes high school students’ ability to become involved in their communities and develop interests that don’t grow out of school experiences.

“I know some people say [homework] teaches kids responsibility, it teaches kids discipline, but there are just no studies that show it does any of that,” she says. “So for me, I like to think that there’s almost a firewall between the school and the child’s family life.”

RELATED: Find Education Resources in Your Area

Homework Alternatives

Back at P.S. 118’s SLT meetings, “parents were asking the teachers what they were doing with the homework,” Hernandez says.

Not much, as it turns out. Rather than grading the homework and using it to plan future instruction, the teachers at P.S. 118 were mostly just checking to make sure the students completed and turned in their homework packets, Hernandez says.

“So we really just kind of sat back and we thought what kind of program can we implement that would be more beneficial to our students, to our families, and to the teachers,” Hernandez says. “At P.S. 118, we really try to put a lot of play and hands-on learning in our curriculum, and so we thought why don’t we extend that into our after-school homework program as well and try to make it more interactive, more play-based, and more hands-on?”

The result of that brainstorm session was Exercise Your Brain, which Hernandez created with Matt Weeks and Laura Willeford, both third-grade teachers at P.S. 118. The three teachers looked to the program P.S. 11: The William T. Harris School in Chelsea, Manhattan, uses, the Home-Based Optional Practice. With HOP, teachers provide families with a list of optional activities (with individual and family approaches to each activity) for every grade level.

“We put together a menu of activities that would hit on a lot of different profiles of learning,” Willeford says. “We wanted to create an opportunity where kids could express their learning and their engagement in school in a variety of modalities.

|

P.S. 118's third-grade Exercise Your Brain menu from November

|

EYB is a menu of activities that changes monthly from which kids can choose an activity to complete. While participation in EYB is not required, Weeks has found that “100-percent of students participate, and they’ve participated a handful of times so far,” he says.

Exercise Your Brain was implemented at the beginning of the school year, and though it met with some hesitation from the parents, the feedback now is positive.

“I remember having mixed feelings, because while I support innovation in education, this no homework idea was foreign to me,” says Debbie Farrell, a mother of first- and second-grade boys at P.S. 118. “My 7-year-old son used to delay starting his homework, or skip it altogether. Now he and his brother both start talking about which EYB activity they can do, even before we are home from school. They are also able to do some EYB activities together, like the science experiment making invisible ink (video below). They seem more patient with each other as well.”

Oliver Stockhammer, father of third-grade Jovan, says, “Maria [Jovan’s mother] and I feel that this program has engaged the children on such a higher level than simple homework worksheets, getting them ownership of the projects, selecting and following through.”

“I’m also seeing [increased engagement] in the classroom,” Willeford says. “My class is probably the most engaged class I’ve had, and I think a lot of that is attributed to the fact that they have been able to be creative and have self-initiated learning.”

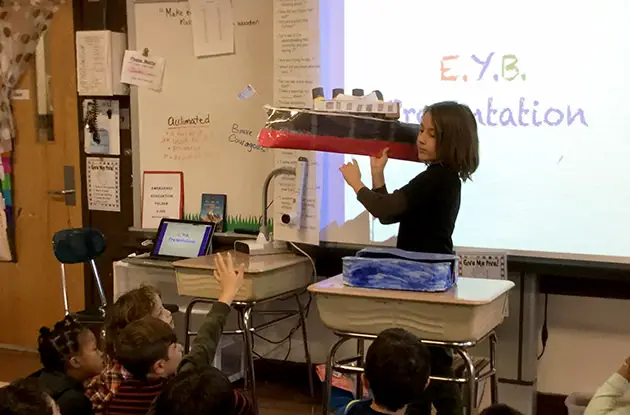

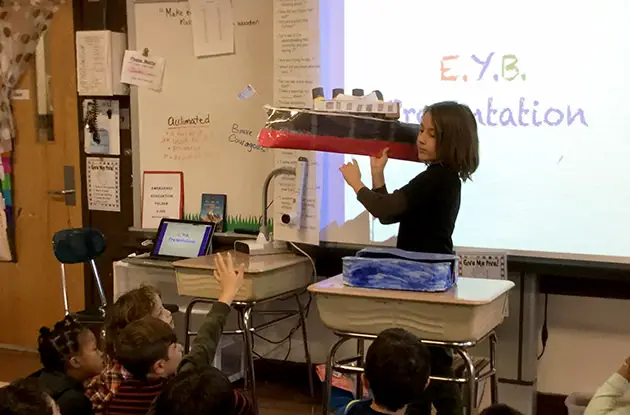

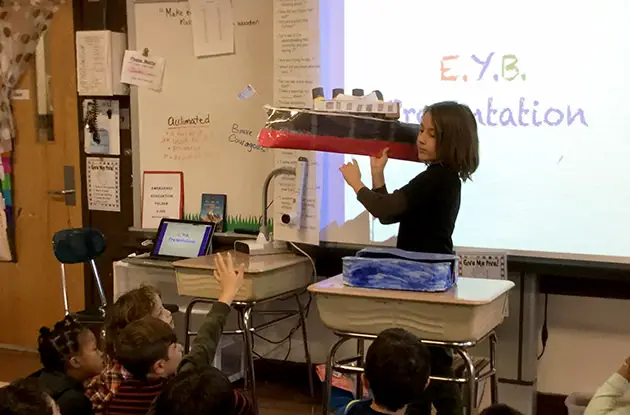

The kids are loving EYB, too. “You have fun with EYB because you’re making something and learning a lot about different things,” Jovan says. “You don’t have to do homework all night long, and you get to present to the class and get to show what you did. With normal homework you just hand it in.”

Making Changes in Your School

The one resounding piece of advice everyone gave: Changing the homework policy at your children’s school should be a major discussion within the school community. Each school “needs to deal with the issue from the context of that school community. It really requires all parents to get involved to try to shape the work at the school so there’s a balance between school life and family life,” Kralovec says.

“You do really have to look at your population, and you need to talk to the stakeholders. Talk to the principal, go to the SLT and make a presentation,” Garraway says. “We talked about it in SLT all last year, and we implemented [Exercise Your Brain] this year because homework just kept coming up” as an issue.

It’s also important to look at how scaling back or ending homework will affect all kids in terms of their performance at school.

“Those who love academics may thrive when there’s more to do. Those who are already disengaged from school may find it even more problematic if there’s too much activity, and then they respond when the homework is cut back, but it may not benefit them unless they’re also given alternate ways to improve their educational performance or to get engaged in academic activities,” Hatch says. “It’s about finding that right balance that allows every student to get the kind of academic support they need.”

Main image: Jovan Stockhammer, a third-grader at P.S. 118: The Maurice Sendak Community School in Park Slope, Brooklyn, presents his Titanic model to his class.

Courtesy Oliver Stockhammer

RELATED: Spend the Weekend Doing Fun Things with Your Family